In the exhibition Der zwanglose Zwang (The Unforced Force) which takes place at Kunstverein Bielefeld

from March 1 to April 27, 2025, the visual artist, set designer, and actor Alex Wissel continues his

longstanding exploration of the origin of anti-democratic and identity-based politics of right-wing

populism. This exploration culminates in new groups of installations specifically developed for this

exhibition.

At the center of the exhibition is the figure of philosopher Jürgen Habermas, representing the

communication theory he shaped, which has significantly influenced the cultural self-perception of

public debates in the Federal Republic of Germany since 1945. In his Theory of Communicative Action,

Habermas argues that the best argument prevails through rational persuasion without external coercion.

Wissel juxtaposes this concept with our contemporary moment, shaped by neo-reactionary thinkers

such as Nick Land, Peter Thiel, and Elon Musk. These figures no longer view freedom as part of

democracy but advocate for a fully privatized public sphere, which Habermas would describe as a

“destroyed public sphere.”

//

The Unforced Force

Our exhibition begins with the 2008 financial crisis. Peter Thiel – tech oligarch, billionaire, PayPal founder – loses a great deal of money. Speaking on a panel the following year, he will announce that freedom and democracy are no longer compatible. "In our time, the great task for libertarians is to find an escape from politics in all its forms."

Whose face is that? Who is the man, turned upside down, who looks at us from the walls of the Kunstverein?

Jürgen Habermas.

The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, born in 1929, is among the most influential of postwar thinkers, best known for his theory of communicative action. The theory argues that a democratic society must be based on reasonable communication which rests on argument and mutual understanding, as well as forms of political decision-making based on just legitimation. Habermas suggests that this kind of democratic debate requires an ideal speech situation, which can guarantee the discussion of opposed opinions and competing perspectives. Only when all speakers are placed on an equal footing can the unforced force of the better argument truly take effect. For this to happen, shared constitutional principles must be assumed to be beyond argument. Habermas’s idea has had a lasting impact on the cultural understanding of public debate in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Our exhibition begins on June 6, 1986, when the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung publishes the article "The Past that Refuses to Pass Away" by the historian Ernst Nolte. Nolte’s essay represents the opening salvo of the "Historians’ Debate," the first public, nationwide debate in Germany about "drawing a line under" the question of the uniqueness of the "National Socialist extermination of the Jews." Habermas’s article, A Kind of Settlement of Damages, published in Die Zeit five weeks later, stands in clear opposition to Nolte’s position. The overall argument is won by Habermas and an associated group of historians, who argue for the singularity of the Holocaust, in this way laying the foundation for German memory culture.

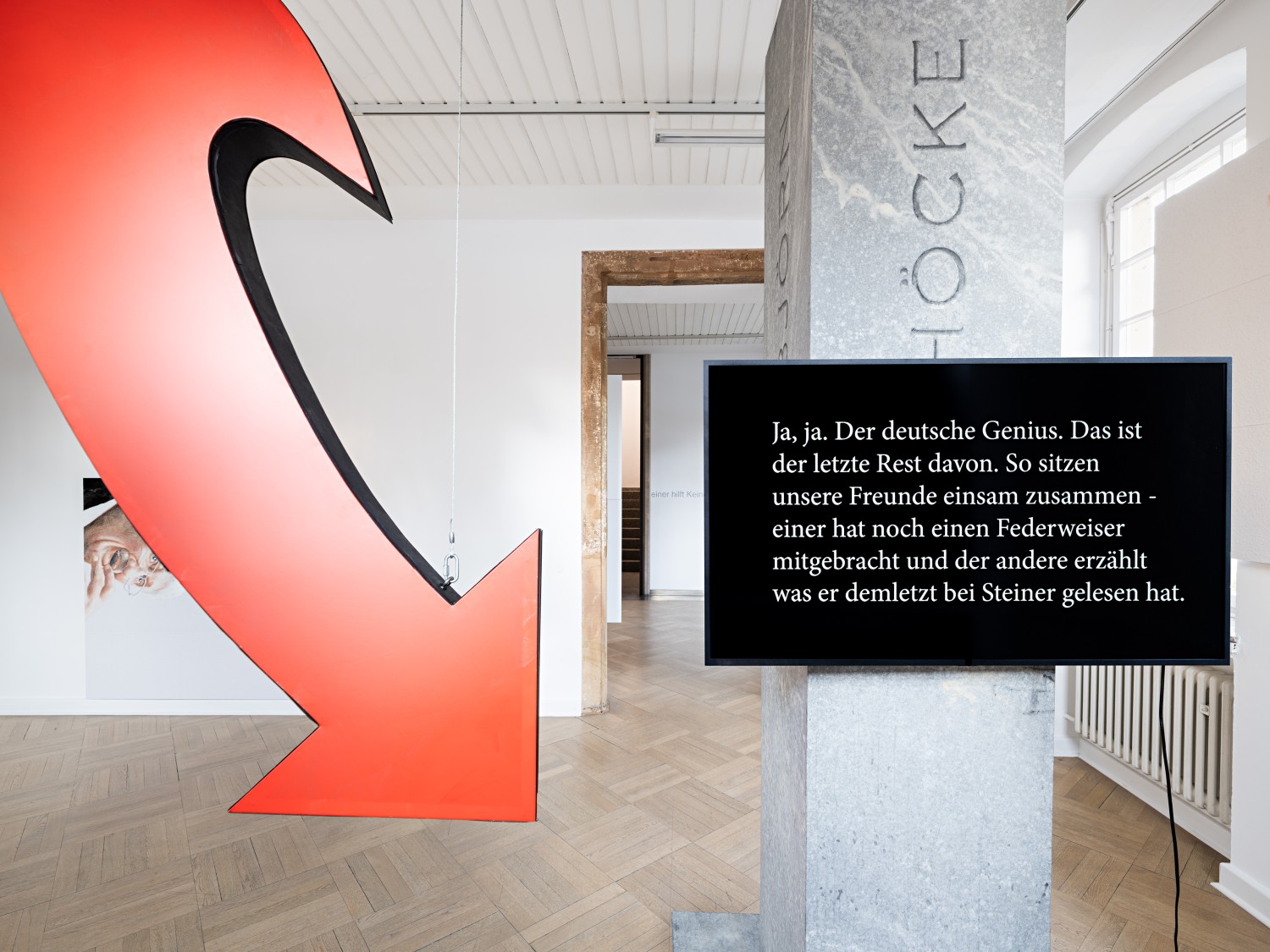

The exhibition features a replica of Martin Kippenberger‘s gravestone, which is also being used, along with the dangling arrow from the logo of the far-right AfD, in the scenography for One Must Imagine Mephisto Happy, a play currently running at the Düsseldorf Schauspielhaus. The exhibition is borrowing both of these elements from the play: they will travel back and forth between Bielefeld and Düsseldorf for the duration of the Kunstverein show. In Bielefeld, the gravestone serves as a projection screen for Alex Wissel’s (b. 1983) film HA HA M.K.B.H. What‘s Worse than Losing?, made in collaboration with the director Jan Bonny. The film is an open process, consisting of fictional scenes, reenactments, and discussions with contemporaries, drawing on and extending the 1970s tradition of history workshops. HA HA M.K.B.H. What‘s Worse than Losing? uses parallel montage to juxtapose actions by and interviews with Kippenberger in the 1980s with more recent actions by and interviews with far-right populist leader Björn Höcke. The aim here is to stage a collective thought process, with a view to investigating this hypothesis: Did the play with signs, attitudes and symbols – the subversive, provocative, postmodern play of the 1980s – mark the beginning of something which has now become political reality, in the form of our contemporary reactionary backlash?

Within this exhibition space, Habermas’s gaze is repeatedly directed toward us: gesturing and tirelessly reasoning. In recent decades, Habermas has repeatedly intervened in public debate, offering a warning message to his listeners. The portraits are drawn on woodchip wallpaper. This surface was not chosen arbitrarily: this kind of wallpaper – comprising several layers of paper containing wood chips – was particularly popular in the post-war period, when it served to conceal construction defects and the unevenness of walls. During Germany’s post-war reconstruction, Habermas criticized the process as too oriented towards technical and economic progress, which underlay its overall failure to carry out a serious social and political reappraisal of National So- cialism. The house was made habitable, so to speak, but its underlying structure was still rickety.

Our exhibition begins in December 2019. Wissel, who occasionally works as a stage designer and supporting actor, is making a plague of boils for an exhibition. The production process is quick: the boils are made of styrofoam and paper-mâché, more reminiscent of carnival dummies than an infectious skin disease. In the years that follow, Wissel will exhibit his boils again and again: his work on them runs in parallel with the country’s political shift to the right. In other words, they look more "realistic" with each exhibition. When working on the boils for the exhibition, Wissel developed an actual rash and asked himself whether he had actually been infected.

Via a staircase, visitors proceed to the Kunstverein’s underground spaces. These rooms are alrea- dy completely overrun with infected plague boils. In a video installation, all of Wissel’s visual research focuses on the question of how, in the nineteenth century, (German) national identity was created a transmedia process, involving artists‘ festivals on a large scale. In this room, the va- rious objects and the boils also make reference to the immediate region around Bielefeld, which features three places of pilgrimage for esotericism and right-wing ideologies in and around the Teutoburg Forest: the Hermann Memorial, the Externsteine (a distinctive sandstone rock formation) and the castle of Wewelsburg.

These places play an important role in the project explicitly pursued by the new Right: "dismantling the Enlightenment" in favor of a "reenchantment of the World." Occult thinking has deep roots in the anti-democratic, neo-feudal philosophies of the neo-reactionary movement around Nick Land, Curtis Yarvin, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe. In the next room, a mannequin wearing an "artist’s hat in the color of Germany" is painting the construction site of the Berlin palace. Like ethnonationalists like Björn Höcke, these libertarian thinkers and "anarcho-capitalists" regard the nineteenth century as superior to the present day, including its superior form of government. However, Hoppe, a student of Habermas, emphasizes that both democracy and monarchy are obsolete as political systems: he prefers a different organizational form, which he calls the "natural order", a system based exclusively on private property, with no national government. In this system, all state functions will have been privatized.

Our exhibition begins in 2022, when Habermas published the German edition of A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics, which reflects on his theses about the public sphere, originally developed in the 1960s, which he here revisits in the light of developments in digital media. Habermas puts forward a diagnosis: the public sphere has become fragmented. What was originally meant to be a plurality of voices has turned into an algorithmic bath, in which users "stew in their own juice," remaining within their digitally-amplified echo chambers, consuming only information which supports their existing views. In October of the same year, entrepreneur and billionaire Elon Musk took over the social media website Twitter, immediately modifying its algorithms to create a revamped platform, which he would later rename X.

A carnivalesque figure is painted on a wall of the top floor of the Kunstverein, dressed in a morphsuit patterned after the American flag. Morphsuits are tight-fitting bodysuits used for special effects in cinema: among other things, they can render the wearer invisible against their sur- roundings. Down on the ground floor, we have already seen other figures in morphsuits, fooling around with various Habermas portraits in a way that is simultaneously anonymous and eye-catching. In the meantime, the images of Habermas‘ face have completely shifted around, disintegrating into individual elements scattered around the room.

The exhibition begins on February 14, 2025: at the Munich Security Conference, the US vice-pre- sident JD Vance gives a disruptive speech in which he calls for the abolition of Germany’s political "firewall" – the refusal of other political parties to work with the AfD – and indirectly offering support to that party in the upcoming elections. Does this mark the beginning of the end of the democratic trans-Atlantic conversation which has prevailed since 1945, the actual beginning of the 21st century? Does it mark the end of Habermas’s life‘s work, dooming his theory positing the creation of consensus through reason?

Our exhibition ends in the upper floor of the Bielefeld Kunstverein. Here, in the final room of the exhibition, we see a central installation, designed by Wissel, along with the visual artist Peter Lober, in 2008, the year of the global financial crisis. Two mirrors, each about human-sized, are attached together back-to-back, each with two holes at eye level. If two people stand facing each other on either side of the piece, they see their own reflection, but they look into the other person‘s eyes, instead of their own.

Bibliography:

Rudolf Augstein, Karl Dietrich Bracher et al., Historikerstreit: Die Dokumentation der Kontroverse um die

Einzigartigkeit der nationalsozialistischen Judenvernichtung, Munich, 1978.

Max Chafkin, Peter Thiel – Facebook, PayPal, Palantir, Munich, 2021.

Philipp Felsch, Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir, Berlin, 2024.

Saul Friedländer, Reflections on Nazism: An Essay on Kitsch and Death, New York, 1984. Titus Gebel, Freie Privatstädte, Moos, 2023.

Jürgen Habermas, A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics, Hoboken, NJ, 2023.

Jürgen Habermas, "Es musste etwas besser werden...": Gespräche mit Stefan Müller-Doohm und Roman Yos, Berlin, 2025.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Demokratie, der Gott der keiner ist, Bad Schmiedeberg, 2001. Nick Land, A Nick Land Reader: Selected Writings, New York, 2017.

Martin Langebach (ed.), Germanenideologie, Bonn, 2020.

Stefan Müller-Doohm, Jürgen Habermas: A Biography, Cambridge, 2014.

Quinn Slobodian, Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy, New York, 2023.

Peter Thiel, Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, New York, 2014.

Stephan Trüby, Rechte Räume: Politische Essays und Gespräche, Gütersloh, 2020.

Michael Cornelius Zepter, Maskerade: Künstlerkarneval und Künstlerfeste in der Moderne, Cologne, 2012.

KUNSTVEREIN BIELEFELD

Welle 61

33602 Bielefeld

Thu - So 12:00 – 18:00

Mo-Wed, by appointment

Closed on public holidays

Closed on easter 18.04.2025 - 21.04.2025

T +49 (0) 521.17 88 06

F +49 (0) 521.17 88 10

kontakt@kunstverein-bielefeld.de